My Journey to Ecuador 2018.

Math Team for the Galápagos Conservancy San Cristóbal, Galápagos

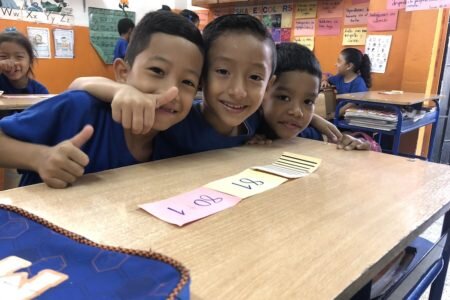

Hope of Bastión School, Guayaquil, Ecuador

USA Today published an article “Teaching: A crisis in Perspective.” There is a distinct contrast between their finding “that teachers are worried about more than money. They feel misunderstood, unheard and, above all, disrespected” versus the primary sentiments expressed by the teachers they interviewed of “I wouldn’t want to be anywhere else. When you help a kid that really wants to learn, when they say, ‘I got it,’ that’s something you take with you the rest of your life.” Despite the state of education, and the pressures educators feel, teachers are dedicated to making a difference in the lives of children. Turns out this dedication and commitment to children is universal. I’d like to share my journey 3,000 miles away to another world where I found so much to be different …. yet the same. And, like the teachers in the article by USA Today, like the teachers in Ecuador, I wouldn’t want to be anywhere else.

At breakfast, I am joined by the famous Darwin finches swarming to share my fruit. My “commute to work” involves stepping around a baby sea lion and passing by a blue-footed booby. The location is different in all kinds of wonderful ways. I am in San Cristóbal, one of the Galápagos Islands, teaching as part of the math team for the Ecuadorian Conservancy. It is year three of this project, and teachers from around the islands have gathered here for one week of learning. The team of educators here to present are from Spain, Mexico, New Jersey, Texas, Quito, Guayaquil, and other parts of the world. It is surreal to be here with this team.

The school where we are working with the K-12 teachers consists of a gated outdoor space. In this space there are separate buildings of classrooms with well worn desks and chairs, some simple shelves for storage, whiteboards and projectors, that may or may not be working. Curtains billow in the breeze, in an attempt to keep out the strong afternoon sun.

This is a simple space with one purpose: to educate children.

For this week, the Islanders are keeping their children home in order for the teachers to work and learn together. I am collaborating in the primary teacher session and able to talk (with the help of a translator) about the importance of learning to count. This is one of my favorite topics to speak about, as counting is far more complex than most people appreciate. I walk teachers through the activities I know resonate with American teachers, and they have the same effect. There is laughter, and aha moments, as teachers are asked to count in nonsense words which helps them to unpack the complexity and gain a deep understanding of the principles for counting.

With some greater insight, we roll up our sleeves and look closely at the activity of counting collections. I share student work and we consider local materials that can be used for counting. We decide seeds, stones, recycled bottle caps could all be available and possible here.

There is a buzz of conversation in the room, half of which I don’t understand as it is in Spanish, but what I do understand is that they are excited and they are making connections.

After my session, Viomar approaches my colleague and shares that she has a student who is in third grade and still doesn’t “trust the count.” He doesn’t see patterns in counting, and she thinks perhaps things have gone awry for him early on in not understanding some of the counting principles we have discussed. She has asked permission to work with him outside of the school day, but the parents have not agreed, and are not supportive when additional work is sent home. She has been at a loss for what to do but is inspired with some new ideas. She talks for a while about what she could try, she shares her contact information, and we connect frequently about her teaching and her students throughout the week.

And in this connection, in this very different environment, I know that I am doing what I was meant to do. I am making connections. I am opening up the conversation. And I am supporting a teacher in the work of educating children. I walk home from the session to be greeted by an amazing sunset with sea lions barking.

Grateful.

Next stop - Guayaquil, Ecuador

We fly back to the mainland to volunteer in the Hope of Bastion School (Escuela Esperanza de Bastión). We are staying in a Marriott in downtown Guayaquil, a short walk to a mall that may as well be here in the United States. We have dinner at a Friday’s restaurant, and the mall is bustling with people watching the televised soccer (fútbol) game with two of the city’s teams squaring off. There are yellow team shirts everywhere worn by intensely enthusiastic fans. The store names are all familiar, as are the expensive price tags. American music, much of it from the 1980’s, plays on the speakers throughout the mall. This is familiar. Comfortable.

The next morning, we take a 20 minute cab ride to a different part of the city. In this short cab ride, everything changes.

We are on our way to La Escuela Esperanza de Bastión which “is located in Bastión Popular, a former squatter community on the edge of the hot, humid city of Guayaquil, Ecuador.

Founded in a time when the community had no public education, the school began as a way to provide poorer families with quality education.” The tall buildings and the frenetic hustle of a morning in a city fades in the rear view mirror as the cab driver weaves in and out of cars, with no appreciation for the lanes in the crowded road. The buildings become smaller and most are still locked up for the day behind gates. We travel through a section of road where there is car wash after car wash, with people attempting to flag down customers. When we stop in the traffic, anything from papaya to toilet paper is being sold as people wander through the cars with merchandise on their shoulders. We arrive.I exit the cab tentatively, as the entrance to the locked school is unclear. Stepping outside of the cab, we are greeted by a strong smell of fumes mixed with waste. It is jarring and takes a moment to adjust.

And then …. I step inside.

There are currently 200 students enrolled in the school. The days are split into primary students (grades 1 - 5) attending from 7:00 - 12:00 and then upper students (grades 6-8) attending from 1:00 - 5:30. It is Monday, and all the students are gathered in a space singing their national anthem. They are all dressed in a blue shirt as their uniform.

As the students file out of their assembly, they recognize me as English speaking, though I have not spoken. One of the older students bursts into a huge smile and says in a thick accent, “Hello, how are you? My name is Ken.” He is beaming with pride about being able to use his English. I return with my English accent in Spanish, “Muy bien, y tú?”

I see Ken throughout my two days in the school, and this continues. He practices English. I practice Spanish. It is a fun little exchange, and I am immediately drawn into the warmth of this place.

On our first day, we visit each teacher’s math classroom. The teachers are genuine, welcoming and smiling. They are teaching from the national textbook, which the parents have purchased for their students, and they are obligated to complete. It is very traditional. Classrooms are sparse, and there is not much creativity to the lessons. Students sit obediently in rows. These teachers hold a teaching certificate and earn the minimum wage of around $375 per month. Most work a second teaching job somewhere else for the afternoon. They are sincere in their efforts with the students, and when we meet with them to discuss their lessons, the conversation sounds very familiar.

In this dramatically different environment, they have the same questions we address in the United States:

“How do I keep my students engaged?”

“I don’t know what to do with my students who are struggling.”

“I am not sure how to make math more interesting or be sure it makes sense to everyone while completing the required workbook.”

The difference here is that teachers have not had the support and the training to answer these questions. I can hardly wait for day two when we can begin the work of answering these questions. We hope to foster a longer term relationship with the teachers in this school.

We visit Vilma, a fourth-grade teacher and learn that her idea of making math fun was to have students race through long division problems on the board.She is aware that this means many others are left out of this activity and wants to know what else she could do. She shares that long division is difficult because the students really don’t know their facts.We are able to leave her with a file of games in Spanish for her students. She tells us she can’t wait to get home and look through all of the games. She also says that she will be traveling to the United States to see New York City in March, and hopes to come to visit us in Boston. My heart grows a little bit.

We next meet Francesca, who teaches first grade. Her students are working with the “eighties family.” They are connecting a visual model of tens and ones, with the written number, and with an addition expression (85 as 80 + 5). She mentions that some of the children are having trouble with this addition fact portion. Together, we create a matching game which she delivers beautifully the next day.

The students are excited as they scramble to find friends that have their matching card. I am able to leave her with more ideas to continue to unpack base-10 knowledge.

We move to one last classroom where Dina teaches fifth graders about prime factorization. She has clearly planned well for this lesson which flows from the students chanting the prime numbers, to her giving notes and examples on prime factorization, to the students working in their workbooks. The students oblige, but it is evident that many are confused. Like Vilma, and like so many American teachers, Dina explains that the students are struggling with their facts and that she has a wide range of ability in her classroom of twenty students.We discuss how she can have students work in pairs and in small groups, and then we introduce a game. With my colleague leading the game at the board, I support the students as we play, facilitating conversation and dialogue.

At one point I am keenly aware that I have lost my self-consciousness about my marginal Spanish speaking skills, and I am in a huddle with the students debating why choosing the number fifteen would be a good next move. "¿Por qué quince? ¿Cuáles son los factores de quince? (“Why fifteen? What are the factors of fifteen?”)

Yesterday in this classroom only one girl participated.

Today the girls are bursting with ideas.

Dina is beaming and taking furious notes of how she can try this herself. We partner Dina and Vilma to play this game together and support each other in moving the conversation to flow from student to student, providing more access for everyone. This is my absolute highlight of the trip.

I return home, and still a week later am relishing in the comforts of home. Clean water. My own surroundings. Hugs from family.

Returning to work, I continue to be struck by how the sentiments expressed by teachers both abroad and at home are very much the same.

Teachers want to be doing what they are doing.

They are asking to be supported and lifted up.

They appreciate even the smallest bit of recognition.

I believe teaching is a calling of sorts that when answered becomes a gift. I am fortunate in my role in educating teachers as I am given the opportunity to build others up in this profession. I am routinely invited into teacher’s practice where I can support them with kindness. This is a true honor and privilege. I hope that the article in USA Today provides greater insight for those that aren’t educators. I hope to see the profession elevated to the level of respect that educators deserve. But even if that doesn’t happen, because some people will just never understand, that’s ok.

I know with certainty that there is nothing more important that we educators could be doing.

Share your thoughts with me at @LooneyMath